- Pendidikan

- Psikologi perdagangan

- Psikologi Perdagangan: BIAS PENGESAHAN

Psychology of Trading: Confirmation Bias

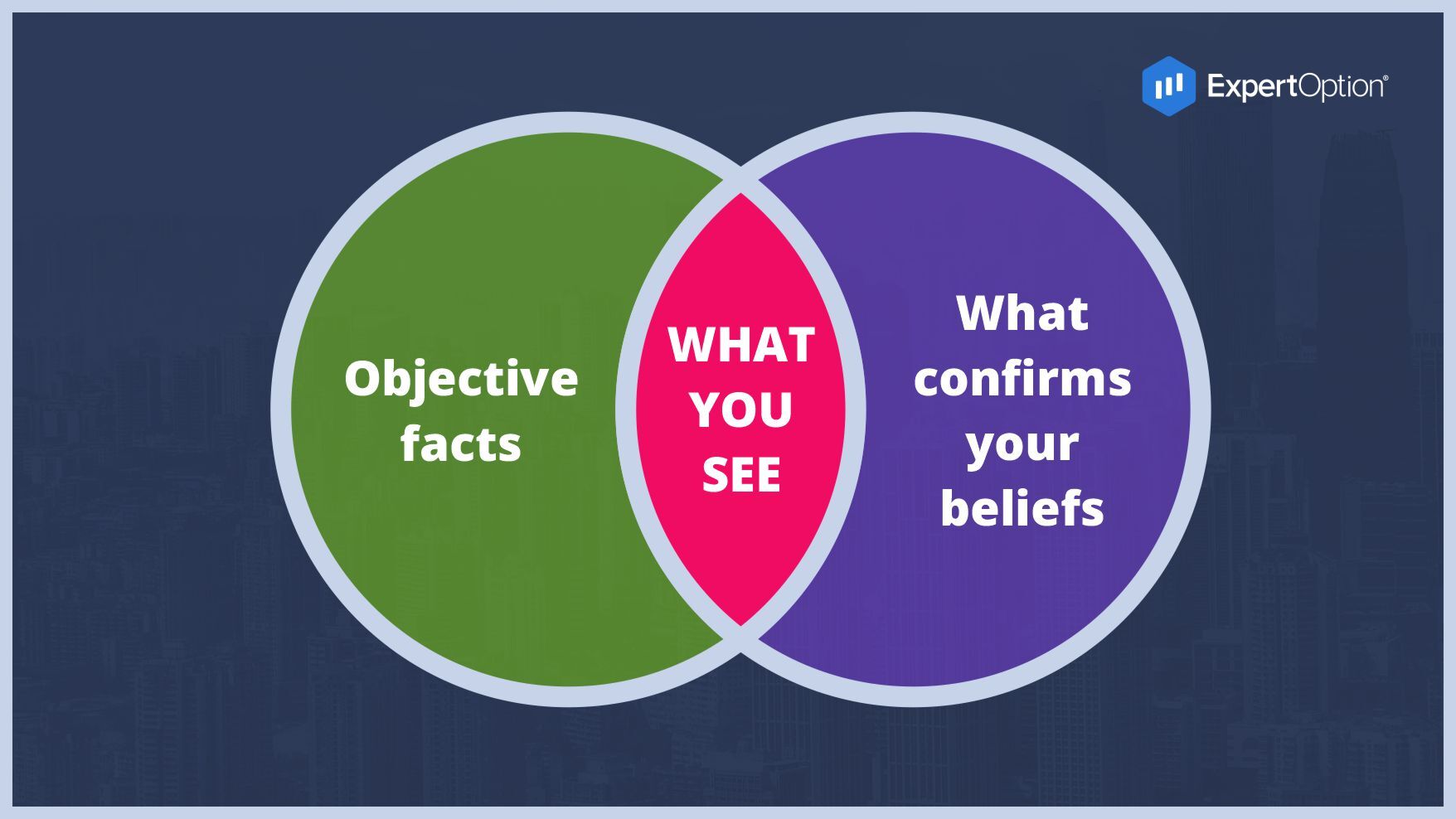

Most people tend to look for information and collect evidence to support a pre-existing viewpoint. We actively seek and attach greater importance to information that supports our hypothesis, while ignoring any evidence that refutes it. Simply put, once we have formed an opinion, knowingly or not, we're unlikely to be objective in gathering information. This tendency is caused by the desire of our brain to find the shortest path to process information efficiently and practically. This makes sense in the modern world, where information is limitless, and the time for making decisions is limited.

British psychologist Peter Vason coined the term in the 1960s. Around the same time, experiments showed that people are prone to validating existing beliefs. Later research has reformulated this phenomenon as a tendency to test hypotheses in a one-way way, focusing on one outcome and ignoring others.

An interesting historical example is Abraham Lincoln, who deliberately filled his government with rival politicians with opposing ideologies. To avoid confirmation bias, of course.

Confirmation bias stems from the existence of cognitive dissonance in human nature. This is the state we experience when two conflicting beliefs are simultaneously held in the brain. There are two main cognitive mechanisms through which we express this principle:

- Most people are afraid of finding out that they are wrong. Problem avoidance encourages us to ignore information that goes against our beliefs, thereby minimizing cognitive dissonance.

- Most people want to know they are right. We seek out information that supports our views, which helps us deal with conflicting data and dissonances that can arise.

Because confirmation bias is a shortcut for the brain, it allows investors to make quick decisions. Investors, as a rule, when evaluating information, ask questions in such a way that only an affirmative answer is possible, thus the opposite data is often overlooked, intentionally or otherwise.

What to do?

Regardless of the evidence presented, if we are unaware of what is happening, we are more likely to interpret the data in a way that supports our point of view. Fortunately, once you acknowledge this contradiction, several strategies can help keep your confirmation bias in check.

- Develop an alternative investment message. This also reduces the likelihood that an investor will reject conflicting information without future consideration. Understanding the critical negative as well as positive factors of any investment raises the investor's risk awareness.

- Search for disclaiming evidence. You should actively seek out people and news sources with alternative opinions. For example, in 2013, Warren Buffett invited hedge fund manager Doug Kass to attend Berkshire Hathaway's annual meeting, expressing views that contradicted his own. Cass was a critic of Buffett's investment style and was short in stocks.

- Responsibility to other people. We are less likely to exhibit confirmation bias if we have to justify our decisions and actions. This is due to our desire to avoid negative feedback or perceptions rather than trying to be more precise.

- Technology is your friend. Probably the best way to combat confirmation bias in investing is through the use of advanced technology. Computers process information in an open-minded and dispassionate manner.